“When you meet someone who inspires your worst angry voice

Just retreat-happiness is always a much better choice.”

Those are the lyrics of musician Michael Franks, words I am often reminded of as I read today’s legacy and social media. Ideally, our civil discourse would be, well, civil, demonstrating deliberation, respect, and a commitment to truth over “truthiness.” Unfortunately, our conversations often devolve into social media “smackdowns,” described by psychologists as “right-fighting.”

Right-fighting is not about reaching a consensus or mutual understanding. It’s about being right, or more precisely, being seen as right. It’s about winning. As Roy Cohn put it, “True power lies in controlling the narrative.” When discussing science and health, right-fighting is antithetical because science is based on uncertainty; we might achieve some consensus, but we can never be certain that we are absolutely right. Right-fighting is a rhetorical weapon in a culture war.

Arguing to Learn vs. Arguing to Win

A 2018 article in Scientific American discussed the contrast between “arguing to learn” and “arguing to win.” In the former, both parties genuinely seek to understand each other. They share views, listen, reconsider, and sometimes shift their positions.

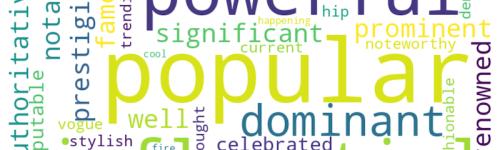

“Arguing to win,” on the other hand, is a bar brawl, all about dominance. It is a performance based on likes, retweets, and snark; for legacy media, it may be muted, but it can be detected in word choice and other subtle biases. The entry of right-fighting into science communication has created a “tribalistic” battlefield, where expertise is abandoned for affinity, facts become suspicious by association, and we move away, not towards consensus.

The Psychology Behind Right-Fighting

The authors argue that right-fighters resist empathy, recoil from ambiguity, and elevate emotional intensity over critical thinking, driven by the fear of being wrong and the belief that wrongness equals weakness. Both sides of our national funhouse mirror reflections on the COVID pandemic feature right-fighters; no political viewpoint can resist right-fighting.

“What the left sees in the right and what the right sees in the left are almost the same: a bullying force intent on imposing its out-of-touch, out-of-whack values on unbelievers and on crushing them if they persist in their heresy.”

― Frank Bruni, The Age of Grievance

According to studies cited in Scientific American, people who view issues through an objectivist lens, believing there is one correct answer, tend to be more closed off to opposing views. But in additional experiments, it becomes clearer that this rigidity, bordering on a moral imperative, may be the result rather than the underlying cause of combative discourse.

In experiments where participants were asked to debate political issues online, those told to “argue to win” came out of the discussion more likely to believe that there was one objectively correct answer and that their opponent was simply wrong. Those encouraged to “argue to learn” were more open to pluralism. In just 15 minutes, the nature of the conversation reshaped their beliefs about the nature of truth itself.

Consider the debates surrounding MAHA, the safety and impact of food on our health, and the multifaceted factors that shape our food landscape. These are complex, evolving areas of inquiry. But instead of acknowledging uncertainty, participants on both sides often double down, lionizing “The Science” as unchanging and absolute or dismissing it as corrupt and agenda-driven.

But the moment we weaponize science to score points rather than foster understanding, we lose the very thing that makes science valuable: its capacity to accommodate uncertainty and self-correction.

The more we insulate ourselves from opposing views, the more confident we become that we are objectively right—and that those on the other side are not just mistaken but immoral, dangerous, or stupid. Today’s social media algorithms tuned to attention foster that insulation. For all that may be wrong with legacy media, it provided a baseline to begin a discussion; its fragmentation leaves us, in the words of Secretary Kennedy, to “do our own research,” an aspirational goal at best.

Is there an antidote to right-fighting? Treating all views as equally valid is unworkable. Debunking, as I attempt to do in my writings, often backfires, at least based on comments, where people double down rather than opening up.

“Human beings often cling to their certainties for fear that their opinions will be proven false. But a certainty that cannot be called into question is not a certainty. Solid certainties are those that survive questioning. In order to accept questioning as the foundation for our voyage toward knowledge, we must be humble enough to accept that today’s truth may become tomorrow’s falsehood."

- Carlo Rovelli, Anaximander

The solution lies in cultivating a culture of “arguing to learn,” encouraging dialogue that prioritizes understanding over victory. Disagreement isn’t a threat, and every conversation need not end in consensus. Arguing to learn doesn’t require surrendering your beliefs; it asks only for humility and the willingness to question. In a world full of noise, the quiet strength of curiosity might be the most radical stance of all.